Markus Appenzeller: Time to Decentralize

Markus Appenzeller is a Dutch architect and urban planner who was also part of the team working on Perm’s Masterplan. Archcouncil’s Portal asked him about transit-oriented development and why it is so important for Russia to have its own experts in urban planning.

— You recently had a lecture in Moscow about transit-oriented development. What can be done in Moscow to implement this concept? How exactly should the transit hubs be reorganized?

— There is not one recipe that would solve all the problems of Moscow. You have to work on several ends at the same time. Making real transport hubs and transport nodes and securing dense development around those transport nodes reduces the need for car use. People can start using public transport more efficiently because either they live closer to a transport hub or they work closer to it. They won’t have to go through endless traffic jams any more.

So you can also approach it from the user’s perspective. What is more convenient for me? Yes, there is public transport in Moscow. But no, it’s not very convenient. Somebody says they live fifteen minutes from a metro station and everybody thinks it’s rather close by. Whereas in London, for example, if you say you live 15 minutes from a Tube station people would say well that’s actually far away.

To me the transport problem is actually the biggest one Moscow is facing at the moment. Working on this will certainly do a great job in improving the quality of life in the city. But we shouldn’t look at it as an engineering problem alone. There are a lot of other aspects to it. We have to change people’s mindsets, to incentivize not using the car and using other means of transport, be that bicycles or be that public transport. It’s definitely one of the most important aspects.

With this goes what kind of development model will you actually pursue. At the moment there is dense development in the city centre but there is also enormously dense development happening outside the MKAD, which is part of the problem. A lot of people live far away from where they work so they have no choice but commuting and with public transport system insufficient or inconvenient they switch to using the car and only increase the problem.

— There has been a presentation of the book “Great Streets” in Moscow recently. What makes it so interesting? Why would you recommend reading it?

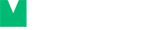

— It basically starts showing that a street is more than just a transport corridor, which I see is still pretty much the case here. Streets here are basically transport engineering whereas “Great Streets” talks about the streets as public spaces, linear public spaces in their on right.

What I think we see now is Moscow in the moment, in the period that all American cities and a lot of Western European cities also went through. As soon as people could afford cars, they bought cars. But that was only nice as long as you didn’t feel the negative impact of cars. And in Moscow now you can definitely feel the negative impact. It’s a matter of time for that paradigm to shift but you can see it already. Parking is not necessarily free anymore. People have to pay for it. There is also an increasing insight into seeing streets as a public space.

— There has been an explosive increase in territory of the capital. How should the transport be developed in New Moscow in order to create a sustainable urban environment?

— At the moment Moscow represents a monocentric model with Kremlin as its centre. It’s like an onion: the further you get to the outside, the less important things become. Jobs are also largely in the centre, and if you go to the outside they decrease. And this is where transport-oriented development can actually help. Moscow needs to look into developing a more decentralized structure. New Moscow could have a number of these decentralized centralities so that people don’t have to go to the city centre any more but go to a local centre instead.

You can see that in London, for example, where there was the City first, where all the banking business was. Then they started developing Canary Wharf as a sort of second business centre. In recent years they strategically used railway stations and old industrial lands around those stations to actually develop new centralities that now form a set of pearls around what used to be the centre of London.

They’re moving from a monocentric model to a polycentric one, and the nice thing about it is that you can start expanding it almost infinitely because people don’t relate to a single centre anymore but they can relate to several ones.

.jpg)

And those centers can be very specialized, like Canary Wharf that is about banking. But there are other areas, which are more about culture, or education etc.

— The topic of the Moscow Urban Forum was the forces that drive the city development. How should an agglomeration be developed in the post-industrial era? Is there such thing as the ideal model?

— We are seeing quite a paradigm shift in how cities are developed and what planning actually does. Until the turn of the millennium planning was more or less a top down thing. The city government decided what happened and where. And they worked together with developers and in some places the public played a more active role in the process by giving comments on that but ultimately it was a top down system.

What we see now is that through social media, through Internet, through global exchange of ideas and thoughts that’s not the case any more.

This whole new way of electronic communication led to the empowerment of the citizens. Saint Petersburg had issues with the Gazprom tower, which people didn’t want to be built; in Istanbul there were protests because people didn’t like the idea of a shopping centre in the city’s most important square. These are all signs that something is changing. Both the public and the government are in the process of finding out what that relationship can be and how they should adjust all systems to accommodate this change in the way they communicate with each other.

There is a certain degree of planning that has to come top down. But there are also other things, and you can give the public a bigger role in defining what happens there.

One of the big mistakes that are often made is that the government feels the need to ask the public — so what do you want? And that is often the wrong question. It should be more like: we have decided to make a public transit system. There will be new metro stations. So what do you think should be located around them? You have to ask the questions that are direct and down to earth. We are experts and we have a strategic view on things. But the average citizen who lives in his neighborhood and goes to work every day has a much more down to earth and immediate relationship with the city.

.jpg)

I’ve seen this in a series of public consultations I had taken part in, for example, in London, when we were working on the Master plan for the use of the Olympic park. The client had big models, and strategies, and long explanations about what we were planning to do, and nice watercolor images so that the project doesn’t intimidate people. And then you get reaction like — yeah, that is all lovely, but what do you plan to do about this fence in front of my house? And it was actually just a construction fence. It was taken down after three years. But this is the level of interaction that people want.

They want to feel they can change their immediate surroundings. The government shouldn’t make the mistake of asking people questions where they don’t really have a say. New tools are needed to better organize the process of interacting with people.

— Can you tell us a little but more about the transport aspect of the Olympic legacy?

— The infrastructure was designed with an eye on how it was going to be used after the Olympics. The Games were seen as sort of intermediate stage, but the end goal was the regeneration of a large part of East London that was pretty much a neglected industrial site. Roads and bridges and sewers and power plants were all designed to serve not only the Olympics but also what would happen after the Games.

That’s one thing. The other is that the Legacy Masterplan in London isn’t a final plan. It’s a framework. The most basic and important settings are there and the rest will fill itself as you go because markets change, demographics change, people’s wishes change, new things pop up that we cannot even imagine now. So the goal is a backbone infrastructure for future development. I think this is what planning is all about.

— You were part of the team creating the development concept for Perm...

— At the moment I worked for KCAP, which was commissioned along with other experts to create a master plan for Perm. We were asked to do something that had never been done before in Russia. So we made a plan that has a lot of elements that come from the Western city planning.

In retrospect I would say there is a number of things I would do differently in this plan. We shouldn’t make the mistake of thinking that everything that happens in the Western Europe can be and should be successfully used in the Russian context.

Investing in capacity building and involving local people is important. So is using us not only as experts who wrote the plan but also as sources of knowledge that can be transferred to the local people. We are commissioned to create a master plan. When we are done, other people carry on. If those people can’t even understand what the plan is about and don’t have the necessary background knowledge, it’s very hard for them to see the aspects of that plan that are most essential to the quality of it.

I’m not advocating applying Western, or Chinese, or wherever they come from concepts in Russia. I hear this all the time — we don’t need foreign experts. But if you have all the knowledge, why do your cities look they way they do?

What you have to do is to develop your own methods, your own system of doing things. I keep saying that Moscow is by far the largest city in Europe. It’s almost twice as big as London, and in terms of scale stands more in line with Tokyo, Shanghai, New York. It’s a metropolis, a megacity. If you look at all those megacities, they have their own DNA, all of them. Tokyo is very different from New York. I think Moscow also needs to develop this.

I don’t think you could say that Moscow is closer to Europe or Asia. It’s a combination of both those worlds. I did this once in a lecture, compared Moscow to Beijing and showed how different they actually are. Moscow is very different from a Chinese city. The way the places are used and organized is very, very different. You are in this fortunate situation where you can take the best from both worlds to create your own. And a city like Moscow definitely deserves this because of its scale and importance. There’s something special about Russia. It’s very hard to grasp what it is but it’s there and you can feel it. This is what genuinely Russian urbanism is or could be.