Dietmar Offenhuber: over 90% of all enquiries and complaints come from about 1% of people

Assistant Professor of Northeastern University Boston researcher and artist Dietmar Offenhuber talks about urban communities and civil discourse, the promotion of urban projects and the implementation of digital technologies in the development of public spaces. The interview took place at the Moscow urban forum.

— What do you think are the most active communities in the modern cities?

— I think it’s locally very different, but there are many different people, both in public sector, but also in private and bottom-up initiatives. On the one hand, I am very impressed with, you know, certain cities and certain city officials who work in a very tight institutional framework to be able to do something and, you know, I mean the Moscow project is definitely very impressive I have to say, the data portal, that’s a very well designed and thought out system. But then there are also international communities of individuals — Zona Maco movement. Last November I spoke at Zona Maco fair in Cairo, so that was amazing just to see all kind of young people who work in all kinds of, you know, public space related ideas and projects. In the U.S. one of the things that kicked off this whole field of civic technologies as the Code for America initiative that brought young people to directly work with cities and in a very bold way. So, ok, this is one problem, it’s a small problem that we can try to tackle. And usually you have new services or start-ups, something that is lasting and not just a hackathon that ends and disappears. So I think there are some encouraging initiatives, in both top-down and bottom-up space.

— How much do you think these communities, single public figures, some activists involved in the matter of architecture?

— It’s funny, because I studied Architecture in the 1990s in Vienna, which was a very difficult time for a young architect, because there was a lot of labor force and not many jobs. So, basically, all of the architects worked in media-related projects and public space related projects. And at the same time when Berlin was kind of the focal point of all these new uses of public space, of temporary uses, suddenly people working with digital media and technologies started claiming public spaces for temporary use and, interestingly, in the U.S. it did not exist until very recently. So, despite now things are starting in the U.S. as well, but Europe... I’m not so much familiar with Moscow, but also initiatives and all sorts of country institutions are also going to the public space to work with media and data — it’s a material to transform the public space, to create kind of ways how all citizens can basically inscribe themselves to the city and basically create a shared space.

I’m very interested in these questions. You know — what makes public space public, and of course there are a lot of legal definitions of what public space is. But eventually it’s a question of experience, how you experience public space. You know, when we think about physical public space, writers like Jane Jacobs and Richard Sennett said that the defining factor of the public space is that you can run into people that you don’t want to meet. So, basically these are kinds of forced expositions to diversity. So, now in digital space we don’t really have that. We only see what we want to see, and we can basically filter out everything else. So one of the key questions for me when we try to bring back the digital projects into physical public space to capture some of this kind of civil antipathy, we are suddenly forced to deal with situations and things that we are not designed and we are not part of the original intention. I think it’s a kind of interesting quality that can lead to new things.

—What are the effective techniques to promote city projects to make this dialog between the government and citizens?

— Well, I mean, I think the first and fundamental technique is to have a dialog at all, that’s already not always easy. But it’s a very central thing...

— What do you think about public hearings?

— So, one criticism that I hear very often about your working with digital technologies is that not everyone has a smartphone and people are excluded in this digital environment. This is absolutely justified and this is something to deal with, but at the same time not everyone wants to go to a public hearing, and not everyone wants to pick up a telephone to basically call. Usually, you know, people who call, at least in Austria where I am from, these are retired people who basically have a lot of time to think about everything that they don’t like about the city.

There are studies that over 90% of all enquiries and complaints come from about one percent of people, so there are just a very few people who are very, very interested in getting involved. And that’s actually a good thing to have those people involved, but in order to raise this percentage, one has to offer multiple routes of engagement. Some people want to write a letter, other people want call to by telephone, other people want to engage through a game, use the smartphone application, other people want to try a public event, they want to be a part of some kind of event or festival. So, I think there are many different ways of engaging and that’s matter of design when it comes into play, because somehow we have to think about all those kind of different things at the same time. And this is, at least in my opinion, a design task. We have to somehow keep track of all of these things to figure something out.

— How much weight do rules and regulations and traditions of urban community life have in it? How often does normal random person think of the idea that the 21th century city demands?

So, the knowledge, skills and abilities because our cities change very fast. They should know that. The way I understand the regulation is from the point of city ordinances and regulatory space. It is something actually very interesting, because it’s different in every city, and this is something people usually don’t think about, because it’s something very invisible, but it’s something that defines a lot of what is possible in the city and what is not possible. And at least, you know, activists and people who organize things in public space are very well versed in how to use regulations and sometimes also twist them and go around and figure out a way of how to use one particular regulation in order to make something possible that would not be possible otherwise.

So, there is a lot of creativity in dealing with regulation, but at the same time regulation is, the city regulations are also something that make a place unique. So we talked earlier about Uber and these kinds of services. If you think about this kind of service, they look the same everywhere on the planet. You open your application and you see exactly the same thing other user will face. But that’s basically what Uber and other companies want to make you believe that is a kind of a uniform solution for all, but it’s very far from the truth. They have to deal and negotiate with every city to, basically, comply with the local conditions. And I think these regulations are actually a good thing, because they really make it possible that there is a kind of a local adapted solution that basically otherwise even if people sitting in California decide effectively how public transportation works in Moscow. That’s also something that you don’t necessarily want to have.

— And, first of all, you studied Architecture. I’d like to ask about the lack of cultural cooperation between the Russian architectural school and European, what do you think about it?

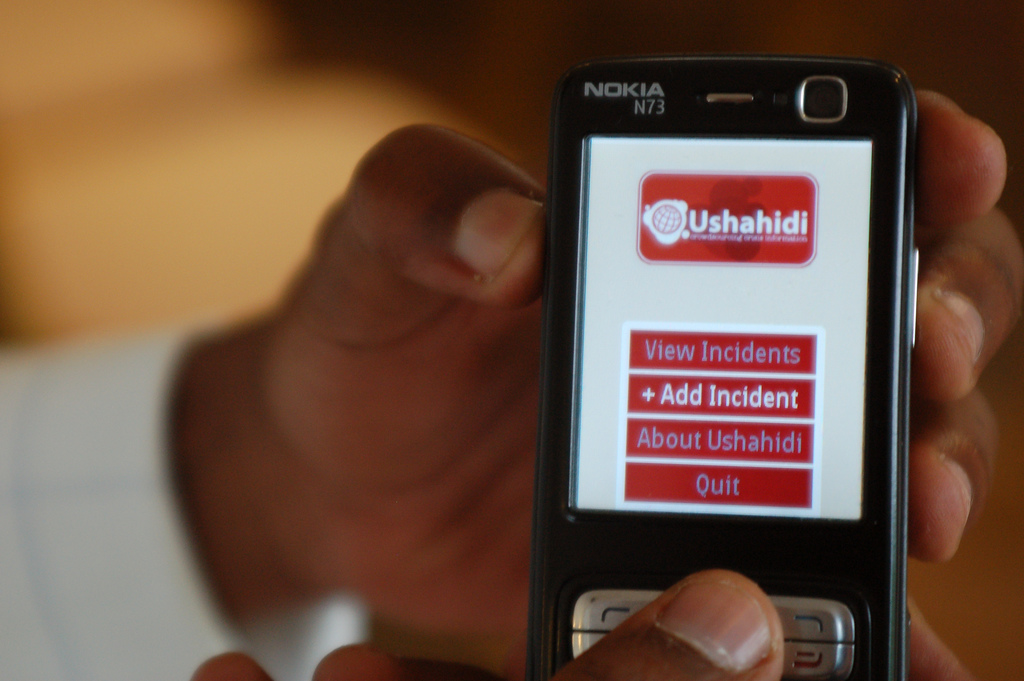

— I think it’s similar for many other countries as well. You know, Austria, Germany, Switzerland, there are architectural traditions, but they don’t really engage in this kind of global community. So language, I think, is one central thing, the language, you know, how you basically subscribe for Austrian and American university. And the reason why I chose this place, because it gives me a lot of different opportunities, so I can go to work with different kinds of universities who all share the same cultural and language space. So, for someone who is now sitting in Vienna or other cities, it’s much harder to become part of that without much effort. So, that’s certainly something. But at the same time if you look at the open source movement and civic technologies, all those initiatives, who only exist and who can only work because they share these international experiences. So for example someone in Berlin might use inappropriate the system that was developed for Chicago or even Ushahidi software developed in Kenya was all the rage over the world.

So, these kind of through to act of making something — you have a kind of international perspectives suddenly, I think that’s not necessarily contradiction with being mindful of the local context because you still come up with a local solution, but at the same time you exchange and you learn from international example. So, I think that’s something interesting and maybe the equivalent of things that are possible within the traditional architecture discipline, especially when we talk about public space.

- Tags:

- public spaces