David Basulto — the pavilions of the Nordic countries and Russia at the Biennale

Founder and Editor-in-Chief of the ArchDaily, David Basulto shared his opinion about curatorial project at the Venice Biennale and the Russian pavilion. The interview took place at the Moscow Urban Forum 2016.

— At the current Venice Biennale you were the curator of the Nordic countries pavilion, which is right in front of the pavilion of Russia. Tell about it and what do you think about this Biennale?

— That Biennale was very special, because Alejandro Aravena set that very ambitious theme, and the whole world of architecture had a lot of hope about this. This was a very expected event, for sure one of the most expected Biennale.

He was also very non-controlling, so he set this very strong theme, and he asked the architects to come back to the opening with what they think that “big front” was to find this big question that architecture need to find the answer to.

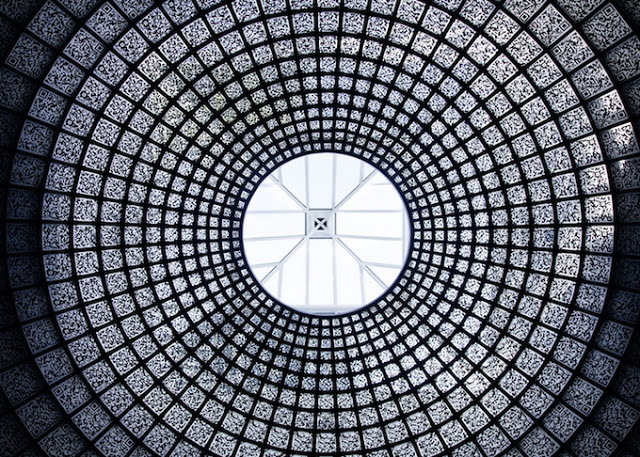

When I got the invitation to curate the pavilion for the Nordic countries I needed some special talent, because these are developed countries that are one step ahead of the rest of the world in terms of education, social welfare, the Nordic motto is “democratic society”. And one may think they have no questions to answer, they haven’t any problems. But you look more closely, even if they have made all this advancement, they are now undergoing many challenges: ageing population, the collapse of the commodity industry that has an impact on how they finance their welfare, the migration problem. So we may say we have something that is very strong, the development that goes hand in hand with architecture and these challenges.

Nordic Pavilion at the 2016 Venice Biennale © Laurian Ghinitoiu

For me there was also a question, if you’re such person, you have problems and you have questions. What do you do? You go to a psychoanalyst. So we decided to find answers to these important questions through something that is similar to psychoanalysis applied to architecture. We turned to certain frameworks of the work of psychoanalysts, such as Maslow’s pyramid of hierarchy of needs, we had three interpretations of that applied to architecture.

In the Pavilion we built this very big pyramid in which we had an Open Call with more than three hundred projects that represent how the Nordic society has been built through architecture. So you’ll have in this pyramid the upgradation of architecture that went from the most basic, the Foundational architecture like housing, schools, and hospitals to the architecture that allows people to be citizens, like museums, public spaces, and sport facilities.

Nordic Pavilion at the 2016 Venice Biennale © Laurian Ghinitoiu

In the upper part of the pyramid is the progress that is very particular to the Nordic society, because it’s progression, so you cannot have one without the other. At first — education, healthcare, and then you can start working on the public spaces. And then in the upper part there is always progress that has a strong relation with the nature — cemeteries, memorials, hotels in the middle of the woods — the progresses that don’t exist elsewhere because of the economic advancement of the Nordic countries.

In this progression we showed the architects what they have accomplished. As for this Open Call, we asked them very specific question, “How has your project contributed to the Nordic society?”

We have all these three hundred projects in the pyramid in the form of stacks of paper; one block is one project, we made the catalogue. That was the first question of the psychoanalyst.

The second question the psychoanalyst will ask you, “How are your parents? What is your relation with them?”

The “parents” of the Nordic architects are very strong masters, like Alvar Aalto or Sverre Fehn, who still carry a very heavy weight on the shoulders of young architects. They present “parents” or “ghosts” for us. Even the Pavilion is a very big “ghost”, this beautiful Pavilion by Sverre Fehn, in which every time the interventions are very subjacent to the building; the building was very precent and the exhibits are always very small interventions. Now we really occupy it. We show that you can really be in very good relation with your “parent”.

Nordic Pavilion at the 2016 Venice Biennale © Laurian Ghinitoiu

So around the pyramid we had the series of rooms with no walls, resembling a psychoanalyst’s office, inspired by Sigmund Freud’s office in London. We laid Persian rugs and very simple steel frames to hold screens — “art mirrors”, in which we presented interviews with the architects that presented their projects for the pyramid talk about this relation, the influence that the masters had had.

So you have the present being conscious of you have done, and you have the past getting into your unconscious; and hopefully through this intervention tool liberate the architects from really big pressure or weight of these “ghosts”.

That’s why you can see that the pyramid follows the same proportions of the existing pavilion. All the wooden steps have the same proportion and the same height as the existing stairs. It’s like an amphitheater having relation to the existing building, but it is displaced from the grid. This pyramid follows many rules of the “father”, but it needs to be a bit rebellious.

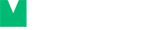

Russian Pavilion. Photo © Vasily Bulanov

For us their perception was weird, because Nordic architects really understood what they have done, that they were influenced. And hopefully, after this exhibition they’ll start to think how to liberate from this past and focus on the challenges of the future.

— And what impression you have from the Russian project? How clear is the concept?

— For me, for the last two years, at last Biennales, Russian pavilion has always been a really good example of impeccable execution and very good design, like exhibition in 2012 by Sergey Tshoban and Sergey Kuznetsov. And this year we were eager to see it, because it was VDNH — a project that many people know abroad. I was lucky to see this fantastic exhibition that is like a timeline of Soviet history that goes hand in hand with the evolution of architecture in the Soviet era.

It was an impeccable execution with all these classical pieces, videos, displays showing panorama of VDNH, and all these classic drawings from the Saint Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts were very beautiful. And I’m sure if you go there and you’ll know about VDNH, you’ll definitely say, “Oh, I’d really like to see it!”

Russian Pavilion. Photo © Vasily Bulanov

But I think the challenge was that for many people it was hard to relate it to the main theme of the Biennale. As for me, I see the relation, because the “front” for the Russian architects would be, in this context, how you can liberate from the strong influence from the past to look forward, because it’s not that you’re going to continue the same very strong propaganda of VDNH. What comes next is that the government of the city took over this project and they want to improve it, recover it, but it’s a very big challenge how to take this piece of history and move forward. So for me it’s a very specific “front” related to the “heavy weight” of the past. When you understand more about the Soviet history, then you’ll see the connection. For sure, in terms of execution and design, this was a pavilion that got a lot of attention. However, for people that don’t know about VDNH it was hard to make that connection.

— And speaking about the main question of our Pavilion. What should be done with the heritage when the ideology is gone and became hostile? What do you think?

— It’s a very big challenge, I think. The good thing is that you have the distance from the look of VDNH in the Soviet times. When you get this, you start to think what will be next. And even now there are some very recent pavilions like VDNH, and if you go there you will start to think like, “We’ve doing this and now we’re going to do the future”, and this kind of task can give you a very good perspective. So I think in this case, you should have a critical view, and the past can really go far away.

— You remember the Russian pavilion 2012 — it was our success, we got even one of the awards of the Biennale. But as far as I know, the Russian architects almost never take part in such major international awards, and at this Biennale there was also no recognition in terms of awards. What do you think, how can we overcome this existing cultural gap between Russian architects and other countries?

— As for me, it depends on communication and flow of information. For example, the Museum for Architectural Drawing by Sergey Choban, it’s in Berlin, but it’s Russian architecture and it is known around the world and won many prizes and awards.

Russian pavilion 2012

Having been coming here for the last five or six years, I’ve seen many buildings that are really new from the traditional ones. So I see there is something a bit hidden, so that’s why the architects are so focused on doing their work here and not taking the hard part for architects to promote their work, entering these award programs, because most of them really need to apply. More and more architect critics and journalists that come here and see the new developments and get very interested.

Then you can think about Boris Bernaskoni who was included in Biennale in Arsenale and the way he got his recognition, because Alejandro asked the architects to apply for this exhibition. They had to write a strong statement in a handwritten form. Alejandro chose Boris Bernaskoni with his project for Skolkovo that is something very interesting, but also it is something you don’t know much about, it was just presented at 2012 Biennale. So these kind of things might be interesting, but the world doesn’t know about them yet.

— Yes, of course. Architects should promote themselves and their architecture to find recognition and get awards...

— What I’ve seen in this evolution is that the city of Moscow is taking architecture like something important. A good example is this forum that brings together people from all over the world: journalists, experts, urbanists; competitions are organized and people are invited from abroad. I think if these things continue to evolve, either the government or architect associations will find the right way to make it grow over time and it’ll be very good for the Russian architecture.

Boris Bernaskoni at Biennale

— One of the topics of this forum is creating architecture of a high quality. So, I’d like to ask what the most effective instruments of architecture activity control you know from the international practice?

— What really helps to push quality is always competition; especially when conditions allow young people to enter, because young architects have a lot of energy and responsibility for doing a public project. They’ll put a lot of effort into doing it, because if they do it right the first time they’ll probably get more opportunities. In that way you’ll get very talented people to fight for that.

In the world practice, in case of Colombia for example, they created very quickly a very strong architectural culture, because the government had very strong plan to recreate a lot of infrastructure in the cities. They did this through a very open competition system that gave opportunities to young architects who really took the responsibility and made the best kind of that possibility.

— And yet most of the buildings that appear on our planet, is created not by architects. They don’t influence this situation...

— Well, now we’re in the urban age with overpopulation problem, and many other things that we discuss here in the forum. We start to think that a big part of that growth is not going to be managed by architects; they’re just going to be slums. You start to think very carefully, like what’s the role of architects?

.jpg)

Museum for Architectural Drawing © Roland Halbe

Because most of those developments are going to be done by not architects, you should turn to work very well in terms of social issue and some relations. The people, who are doing that, thanks to the Internet, get more access to architectural knowledge and information and in that very indirect way they learn from architects.

So the challenge has always been how to get more architecture into informal settlements. I don’t know about the matter of regulation, but architecture is important there. I think informal settlements can be influenced in this relation and architects could really be part of that.

I think especially in this Biennale you started to see more architects who’re involved in that.

- Tags:

- Biennale