Weapons, Bribes, And Dictators: Where Architects Draw The Line

Zaha Hadid says it’s not her job to pay attention to how many migrant workers die in the construction of her world cup stadium. We asked four top architects — Bjarke Ingels, Liz Diller, Clive Wilkinson and Curtis Fentress — how morality fits into the process of accepting or rejecting a commission.

Earlier this year, Zaha Hadid kicked up a firestorm by saying that huge numbers of worker deaths in Qatar — where the renowned architect has designed the Al-Wakrah stadium for the 2022 World Cup — are not her responsibility. The International Trade Union Confederation estimatesthat 4,000 migrant workers will die in the construction boom leading up to the World Cup due to horrendous working conditions. “I’m not taking it lightly but I think it’s for the government to look to take care of,” Hadid said. “It’s not my duty as an architect to look at it.”

Hadid’s assessment of the situation was pragmatic. She has little control over Qatar’s kafala process, a sponsorship system that ties migrants’ visa and legal status to their employer and has been likened to a form ofslavery. But designing a structure that will be built within that system, where hundreds of workers have died in the past two years, is a loaded proposition.

Al-Wakrah stadium by Zaha Hadid Courtesy of Neoscape

Al-Wakrah stadium by Zaha Hadid Courtesy of Neoscape

Architecture does not exist in a vacuum. Moral ambiguities can arise at every stage of the building process—from who you’re willing to take on as a client, to what kinds of structures you’re designing, to who will actually build it (and under what conditions). Would you build for a dictator? Would you design a prison? Would you build in a country that has exploitative labor laws?

Co. Design asked several architects, “Where is your moral line?” Here’s what they had to say about their view on how moral and ethical duty fits into the field.

CLIVE WILKINSON, CLIVE WILKINSON ARCHITECTS

The Los Angeles-based Wilkinson says his firm considers every project in the context of the community around it. “We feel if it’s not making a positive effect on the community, it needs to be reconsidered,” he says. “We’ve been invited into projects abroad where we had to say to ourselves: ’Does this make a positive contribution to the local community?’”

He also says his firm won’t pursue “ego projects” and that they try to balance the needs of the client with those of everyone else with a stake in the end result — like the employees, patients, or students who will be using the building. “The architect’s dilemma is, how do you reconcile the needs of all the different stakeholders, given that only one of those stakeholders is hiring you?”

LIZ DILLER, DILLER SCOFIDIO + RENFRO

“Our responsibility is to use architecture as an instrument of positive change,” Diller tells CoDesign. On the one hand, that means DS+R doesn’t build weapons factories or create designs that glorify dictatorship. Yet architecture can also serve as a critique, and Diller explains that “projects that appear morally dubious at first glance may be camouflaging radical, progressive ideas.”

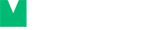

Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s Winning Proposal for Zaryadye, Moscow

Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s Winning Proposal for Zaryadye, Moscow

The firm recently won a competition to design a park right in front of Moscow’s Red Square and the Kremlin. It was a project the firm didn’t take on lightly, since “there was a fine line between celebrating the history of the site and celebrating authority,” Diller says. In response, their design emphasized public assembly, with a pathless park that allows people to wander. Diller describes the design as “standing in stark contrast to the regimented grandeur of Red Square.”

DS+R is also building a factory town in China that will house 5,000 workers, a choice that might appear to clash with the firm’s ethical stance. Diller explains:

At first glance, why would an architect step into an industrial culture that abuses labor under inhumane conditions? But the client is a humanitarian who, by integrating cultural and educational programming, aims to convert blue-collar workers into the white-collar work force within three years. The architecture is a big part of the solution.

CURTIS FENTRESS, FENTRESS ARCHITECTS

“I think architects make a lot of conscious decisions about the building types that they work on,” Fentress says. “We certainly have in our practice.”

His Denver-based firm does not design jails, for instance, and has turned down other projects that don’t align with their views. “There is one project we did turn down for moral reasons recently,” Fentress explains. “That was a grow center for marijuana.” At the time the project was proposed in 2012, only medical marijuana was legal in Colorado, though recreational use was expected to be legalized. The client was interested in building a facility to grow and distribute different varieties of marijuana, where people could come and have a kind of wine tasting for pot. “l don’t think that’s a great idea to legalize it, so we took a stand and turned that piece of business down.”

The firm has also turned down clients “because we felt that perhaps they were not on the up and up.”

Fentress Architects does work in the Middle East. “We’ve done a lot of work internationally. We’ve worked in Qatar, we’ve worked in Dubai, we’ve done 10 buildings in Kuwait,” he says. “To my knowledge, we haven’t had huge safety issues or labor issues for those projects.”

BJARKE INGELS, BJARKE INGELS GROUP (BIG)

“I really do believe that, as architects, we can contribute to a local situation in ways that will be productive for society and for the betterment of the life of people living there,” Ingels says. This guiding principle is why BIG takes on projects in places, like China, that don’t necessarily adhere to democratic standards.

National Library in Astana, Kazakhstan / BIG

National Library in Astana, Kazakhstan / BIG

The firm “desperately attempted” to build a national library in Kazakhstan, despite the fact that “arguably their elected president was as close to a dictator as they come,” Ingels says. “My thinking was, by making a library for the citizens of Kazakhstan we could reimagine a public institution there. We were willing to give it a shot because we believed we could improve things.”

The project eventually fell apart, but not before Ingels encountered the corruption involved in building there. He was asked for multiple bribes. “There are certain countries where you cannot really operate unless you’re willing to play the game, which we’re not.”

The firm has also opted not to contribute to the manufacture of weapons. BIG dropped out of a project designing a photovoltaics lab for a Korean conglomerate when the stock prices for photovoltaics (a method of generating electrical power) plummeted, and the company decided the building would be used to make technology to guide robotic missiles.

“The problem about arms is, you don’t know what they’re going to be used for,” Ingels says. “We wouldn’t want to be in a situation where we would have contributed to making weapons that would be used in a conflict in some sort of a way we couldn’t account for.”

- Tags:

- Zaryadye |

- parks |

- competitions