Philipp Meuser: Moscow Needs More Discussions on the Typology of the Urban Structure

Architect, the author of studies on the history of mass housing construction, the founder of the publishing house DOM Publishers Philipp Meuser told the Archcouncil about the new arrivals of the publishing house and discusses the problems of the Russian typology of mass housing.

— What are the new books for Russian readers recently published by DOM Publishers?

— I would like to present a few new titles, which are somehow connected with Russian architecture. So, we have this book called ArchiDrone in the Russian edition with 70 buildings which have been taken from above, from the angle of 90°, 70°, 45°, and from the street view. And I think this is a very nice title, because now we see a Moscow you have never seen before. The images are by Denis Esakov. There is also the introduction part written by Karina Diemer. She is an art historian, and she wrote a very nice text on the history of aerial photography in Russia. The book is published in three languages, so, we have three different covers.

— You have recently presented a book on Melnikov House....

Yes, it was written by Pavel Kuznetsov. It tells not only the story of the house but also of how to transform this family home into a museum. It is very interesting, because they are describing what should be kept for a museum and how it should be presented. The pictures of the interior in this book are by Denis Esakov. There are all the signs of an architecture museums, so, it’s also a process of becoming a museum.

Another interesting book is a collection of photos of Ukrainian Soviet mosaics. We did it together with Ukrainian publishers from Osnovi Publishing. The photographer was traveling 13,000 kilometers around Ukraine and collecting more than 1,000 mosaics. He selected around 200 mosaics for this book. This book is, of course, a memory of the Soviet Union, but I think it’s also a very nice and beautiful project, which is a nice contribution to the Soviet Modernism.

—

Could you tell us about the re-printed Sotsgorod? Why did you choose this theme?

— Because, in my understanding, it’s one of the most important books written in early twenties in the Soviet Union. It influenced the whole system of city planning and town planning in Soviet times. It was published in 1930, and became a forbidden book. People were not allowed to read this book.

— Who is the author?

—Nikolay Milyutin. Somehow it was hidden...

— Because it was very avant-garde...

— Yes, it was too much avant-garde architecture. But then the concepts of city planning could have been so modern; and if you compare some of these works, which were presented in Milyutin’s book, with some designs from the 50s and 60s, you can see that the Russian avant-garde in the 20-ies was at the level of the international architects. It was the same theoretical circle and everything was reconnected and influencing each other.

—Do you think the ideas of Sotsgorod are relevant now? Are these principles applicable to the today’s reality?

— I don’t think so. In my understanding, these are not the most contemporary ideas, but it’s interesting to understand the Soviet architecture, and especially urban design and urban planning. You need to know Sotsgorod to understand what was happening in the 20th century. The main idea is that city planning is also a process of industrial factory.

— Like in Ville radieuse by Le Corbusier?

— Yes, of course. It was the idea in the 20th century that the city planning and architecture, or let’s say the whole planning and construction, should be industrialized to match the industrialization of the society. So, there was this idea that everything should be newly invented and mass-produced. This trend was transferred to city planning and architecture, and Milyutin was pushing this idea through.

—But that fits only to the type of a city where we have some core factory and some village with workers?

— Yes, it only works for a mono-city. In the Soviet Union, especially in the 60s and 70s, there were so many mono-function cities that had been built just for mining coal or diamonds, or other resources. They had only one function: the city had to make money, to make profit out of the resources. Once the factory was closed there was no sense for the city to survive.

—Can one renovate these cities, adapt them to the modern economic and social reality?

—That is exactly the problem with all modernistic architecture and urban planning. It is very artificial.

Le Corbusier’s buildings and city planning ideas only work if you keep them like they were produced and designed originally. If you start adding something, if you start transforming them, you destroy them.

That’s why I’m saying they are too artificial; they are artwork. They are artwork on a very high level, but they do not really fit the usage or the function of today’s society. If you start transforming it, you have to transform it in a very strong way. You have to take another pattern or another layer and put it on top of the existing city, and then it might work. You can also transform these socialist cities with linear houses: if you just close a block of two linear houses, then you can transform them into a block city. But you may completely destroy the idea of this open landscape where buildings are stand-alone objects. This is my position.

— What if we talk about khrushchyovkas?

— If we refer to the current discussion in Moscow, in my understanding, it is a completely different discussion because it refers to the question of human housing and the history of the social network. The social structure of these areas will completely change. Today’s Moscow is a different typology of the city. The areas where khrushchyovkas stand today —in some places they stand in very central areas— have inner city residential buildings, but the density is very low. In a socialist city it doesn’t matter what the city center is and what the outskirts are because land belongs mainly to the state — the land is not product that you can buy and sell. But Russia has completely changed; and the situation of these low-density areas doesn’t fit this new economic structure. On the one hand, there is a demand, there is pressure on the market; on the other hand, and there is an existing situation with the obsolete neighborhoods.

That’s what I say, you should destroy khrushchyovkas; but some should be kept because we learnt from the city planning in 20th century that it’s so important to keep some areas.

— Keep them as museums?

—No, not like museums; you need to preserve the social life, social neighborhoods.

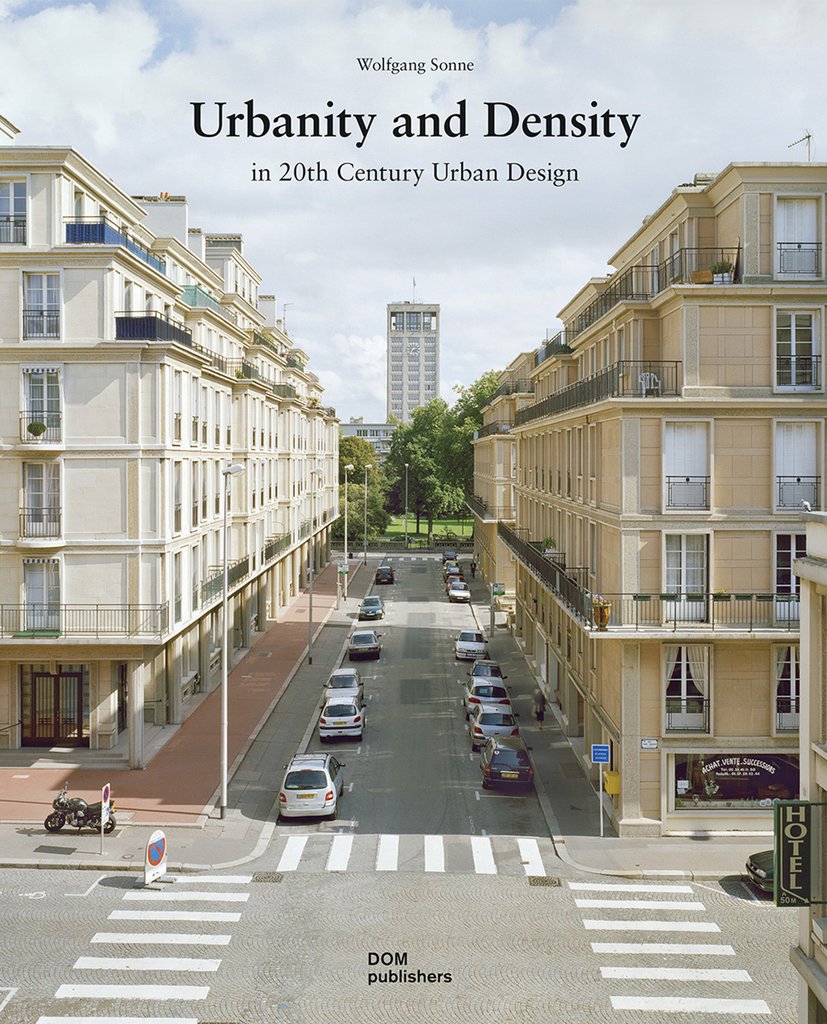

— By the way, you have a separate, very big book on density. Whatisitabout?

—It is a completely different topic. This book Urbanity and Density: In 20th Century Urban Design is in a complete opposite to Sotsgorod. Sotsgorod is mono-functional linear city with low density, and very green inside, and this book on urbanity is on the other tendency what we had in the 20th century, which was to have traditional urban cities. In these «European cities», the property is divided and you have different owners who built the building.

Another difference is that these buildings have the façade, which forms a dividing layer between private and public space.

For example, there is a building is just standing on the border of this plot, and then you have this pedestrian area and the street, pedestrian area and another façade. Private buildings create a public space.

—This is what we are striving to do in Moscow now.

—Yeah, that’s what I see in your plans. The distances between the buildings are very-very small. The closer you put buildings together, the better is the human scale inside. The proportions of the structures should not press on people. We can see only these 6 floors, but if you just compare it to 20 floors, you need a different distance.

—Who is the author of the book?

Wolfgang Sonne, professor of history, urban planning and architecture, lives in Dortmund.

—How can one determine the comfortable limit of density in the city?

—It is all about a high level of comfort in urban neighborhoods. So, if you live in a building 20 floors high and you have an elevator to come down and on the ground floor area you find everything what do you need for your life, then you have a short distance to your work, short distance to kindergarten, short distance to the school, then it’s comfortable.

The needs of the human being are very simple, and are not related to all these intellectual discussions on the model of development of post-socialist cities. Most people don’t care about what kind of topology they live in, they just want to know: Where can we invite friends? Where is the entrance? Is it safe? Do I have enough light? Do I have a comfortable flat? It’s very easy, because people have different interests — not all of us are architects and urban designers.

In the end, what really matters is the urban scale, the possibility of the approach of how each building is creating some kind of facade for the public space.

If the scale is too big, the walking distance is too long, and we don’t have a possibility to go just by car or whatever, then you have to consider making it denser, otherwise, we will go back to the socialist times. Of course, these khrushchyovka areas are difficult to be made denser. Because if you have two khrushchyovkas and put another khrushchyovka, let’s say, in between them — it is just too close. We need to find a new typology, a new construction base.

— We need to provide different options of block organization because right now we have a topology of the urban pattern, which very much reminds me to what we know from the Soviet times: huge microraions given to one developer, one construction company: they just build it pattern by pattern. Russian urban designers need to create their own typology and say, «This is our Russian city.» Let’s not call it a post-socialist model, just call it the Russian typology of the city. We can call it the Eurasian topology because you find it in Russia, Ukraine, the Caucasus, you can find it even in Central Asia. There is a big difference of what we have in European cities. If we have big blocks they’re divided into smaller plots, and each plot has different owners, and different owners are building different buildings. In the end, we have one community of blocks, but in fact it’s a single building.

— But who are the owners of the land?

— The citizens themselves own this land. Let’s take, for example, the area where I live; we own this piece of this building. So, these are 47 different plots. Each building belongs to a different owner. When there was a construction site, it was 47 different construction sites; so, everyone was responsible for their own building. In the end, it looks like a big block but everything is different.

But they are some other strategies, where the state owns the land and gives it for free for 40 years or for 99 years. You just rent it at a very low price, and that of course is an instrument by the state meaning, «We would like to develop this area, the land belongs to the state, you rent it, let’s build a house over there.» Of course, there are some strategies and instruments for developing and designing some necessary facilities.

—And Europe, probably, doesn’t have the large-scale construction like in Moscow...

— Of course, what is going to be built in Moscow has a completely different scale than what we know in Europe. I remember that ten or fifteen years ago in Germany, we had a long discussion on how to solve the problem of our cities shrinking. We still have areas where the city population is getting smaller and smaller. This is a completely different situation. As far as I know, Moscow has grown by 60% in the past ten years. It is very different from Western Europe, where the cities, more or less, stay the same and have a very slow increase in population.

- Tags:

- residential |

- renovation |

- urban design